Dzichava Nhoroondo

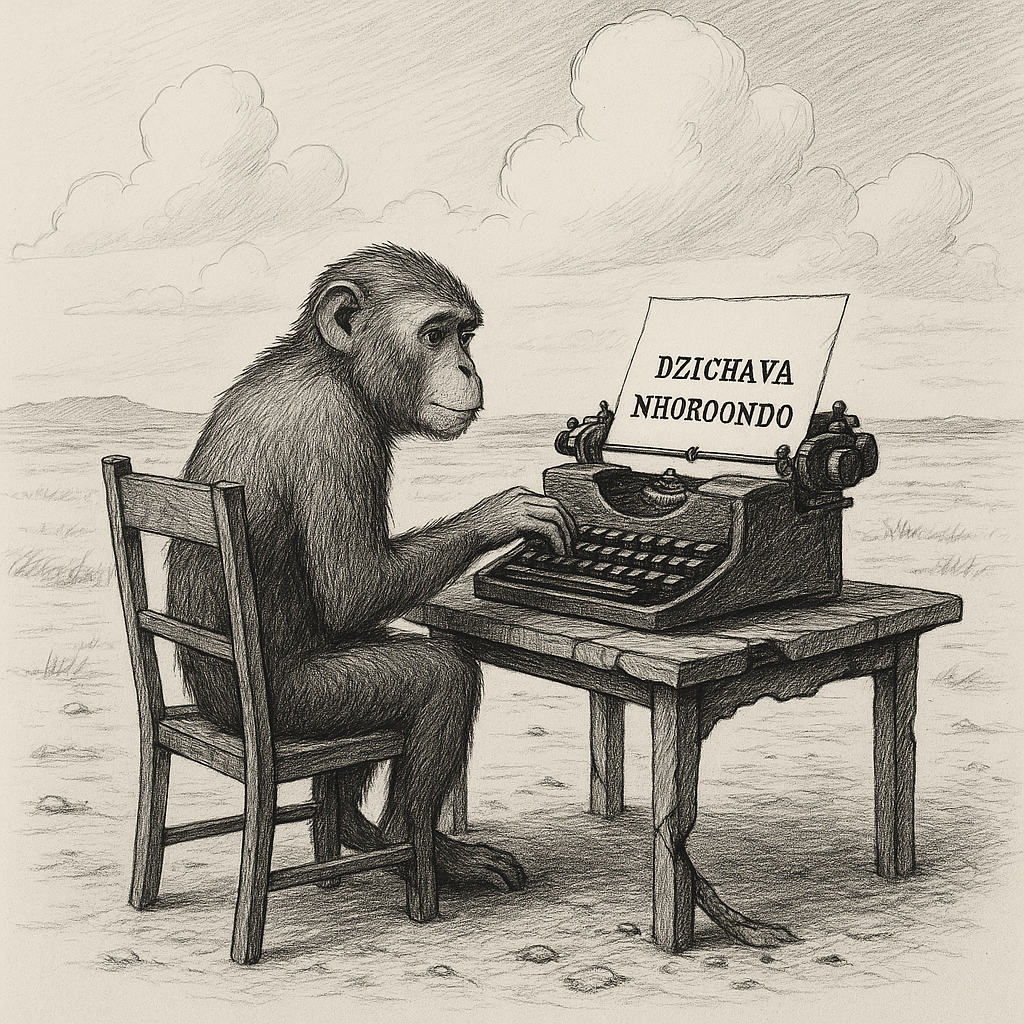

There’s a thought experiment that goes like this: An infinite number of monkeys with an infinite number of typewriters and infinite time will eventually type out the complete works of Shakespeare. But they won’t stop there. They’ll also type out the answers to every question humanity has ever asked, the unified theory of everything, and the password you forgot last week. Somewhere in that infinite stream of randomness, everyone’s entire life story is written, word for word. Yours too.

But here’s the twist—the monkeys don’t know what they’re writing. They aren’t trying to create Hamlet. They’re just hitting keys. The meaning, the beauty, the structure—that comes later. It’s something we find, after the fact, when we sift through the chaos and decide something was significant.

Meaning, in this experiment, isn’t written into the moment. It’s something we recognize retrospectively.

A little over a year ago, one of the smartest monkeys to ever live typed out something.

It all started with a failure. A Power Electronics (EDF) test. Not a life-shattering tragedy, but at the time, it felt like the universe had folded in on me. I don’t even remember the details—which tells you how little it means to me now. I blanked on the basic circuit diagram of a boost converter, something I should’ve known in my sleep. In that moment, a single, random-seeming event threatened my confidence, my future, my whole carefully constructed identity.

So I did what anyone would do: I studied like my life depended on it. And I made a war cry—maybe a prayer—in a language that feels like home. I set it as my lock screen:

Dzichava Nhoroondo.

It shall be history.

It was a promise to my future self. This pain will pass. This struggle will end. Every morning, I saw it. Every night. And it worked (well, I did most of the work). I passed. Life stabilized. The lock screen faded into the background, a relic of a battle won. For a while, it meant nothing.

Until it did.

Because then came project deadlines. The existential dread of graduation. The dizzying highs of success that, inevitably, settled back into a baseline of normal. The phrase wasn’t just a mantra for surviving the bad anymore—it was also a warning about the good. That, too, shall pass.

My promise had turned into a profound, unsettling truth. A double-edged sword. It kept me grounded, but it also felt like it kept me from flying. Every emotional extreme, I realized, is eventually followed by a return to the mean. Everything started seeming the same—all Nhoroondo, all history—without being inherently good or bad. And sometimes, it felt like the average of it all was nothing.

It was around this time that I stumbled into the work of Albert Camus and felt an unnerving sense of recognition. He gave a name to the feeling I couldn’t articulate: the Absurd. The Absurd, he said, is born from the collision between our desperate need for meaning and the "gentle indifference of the world."

My test failure was a perfect example. I had needed it to mean something—that I was a fraud, that my future was doomed. But the world didn’t care about boost converters. It was just… indifferent. My panic was my own. Realizing this wasn’t depressing; it was liberating. As Camus wrote in L'Étranger:

"I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world."

This is the hidden wisdom in Dzichava Nhoroondo. It shall become history—not because life is meaningless, but because meaning moves. It’s not fixed in success or failure. It’s found in the living itself.

"I had lived my life one way and I could just as well have lived it another. I had done this and I hadn’t done that. I hadn’t done this thing but I had done another. And so?"

And so?

That’s the final, quiet evolution of my lock screen. It doesn’t promise a happy ending or warn of a sad one. It just states a fact: It shall pass. And so, the only thing left to do is live.

So How Do We Do It?

"If something is going to happen to me, I want to be there."

Don’t run. Don’t anticipate. Just be present for it. Be there for the panic, and be there for the relief.

Everything passes. The failures. The wins. The night-before-the-exam panic attacks and the "Aha!" moments in the lab. The friends, the jobs, the hobbies, this very blog post. Camus would call this "living without appeal"—without constantly begging the universe for a final judgment or a higher meaning.

Laugh when it’s funny. Cry when it hurts. Learn the circuit diagram. Forget it. Learn it again.

And just let the monkeys type.