I don't know about you, but I've built entire mythologies around people. A teacher, a mentor, an artist. You see a light in them and mistake it for the sun. You expect them to be above the petty, messy business of being human. And then one day, they do something disappointingly, unforgivably normal. They get bitter, or they sell out, or they just show themselves to be flawed. The pedestal shatters. And the silence that follows feels a lot like a crisis of faith.

What do you do when a hero reveals their humanity? When the miracle you were counting on fails to arrive?

There's a part in an old, sprawling Russian novel that wrestles with this exact feeling. The Brothers Karamazov doesn't give you neat theology. It gives you rot.

In the book, there's a young man who has staked his entire life on the goodness of his mentor, a monk so revered that people expect him to be declared a saint upon his death. The ultimate proof, they whisper, will be a miracle: his body will not decay. It will be pure, incorruptible, a sign from God that this man had transcended ordinary flesh.

The mentor dies.

The body not only decays, but it does so with an almost malicious speed. The stench of corruption fills the monastery, a foul, biological fact that suffocates all the whispers of holiness. The cynics are delighted. The believers are horrified. And the young man, the devoted apprentice, feels the floor of his world fall away. His rebellion isn't loud. It's a quiet, cold despair. He walks out of the monastery and decides to find someone "wicked," as if to confirm that the whole project of goodness was a fraud from the start.

So the young man, lost in his doubt, goes to see a woman the town considers a seductress, a source of chaos. He goes there looking for sin, maybe to lose himself in it. But instead of a caricature of wickedness, he finds another person in pain. And in that moment of shared vulnerability, she tells him a story.

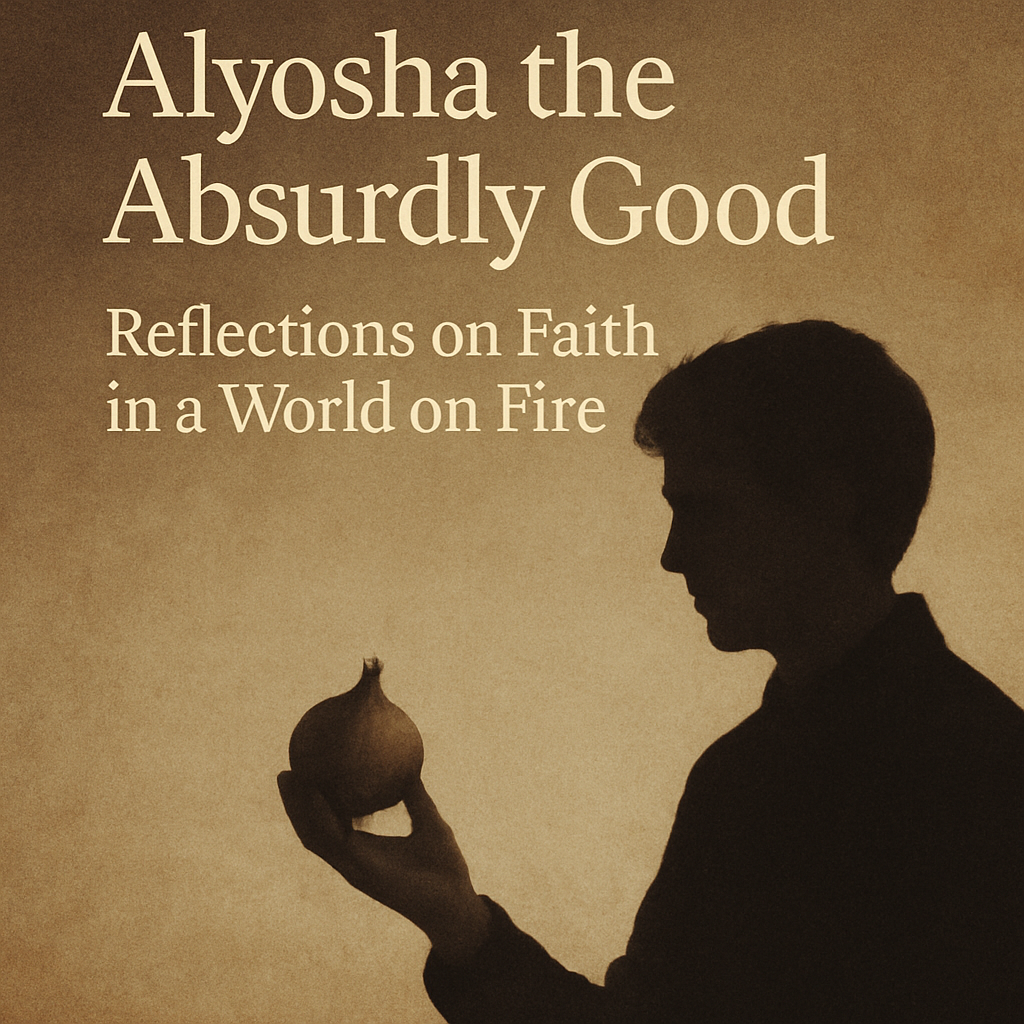

It's a folktale about a cruel, selfish woman who dies and goes to hell. Her guardian angel, desperate to find a single good deed she ever performed, finally remembers one: she once gave a beggar an onion. Just one. God says the angel can use that onion to pull her out of the lake of fire. As she's being lifted, other sinners grab onto her legs, hoping to be saved too. "Let go!" she shrieks, kicking them away. "It's my onion, not yours!"

And the onion breaks.

She falls back in, and that's the end of her story. But not the end of this one. Because by sharing this tiny story—this "onion"—the woman offers the grieving young man a moment of connection, though not in the way she understands it herself. She even admits she's just like the woman in the tale, cynically noting that she's learned the lesson: don't kick others away when your turn for salvation comes. But for the young man, her calculation is irrelevant. What he hears is something else entirely. It isn't a miracle. It isn't a sign from God. It's the revelation that all anyone has is a single onion. In that moment, the "holy" man and the "wicked" woman are the same, and he sees that his path isn't to be above it all, but to be part of it—to always forgive, to always ask for forgiveness, and to always see the onion in others.

Can one good moment outweigh a thousand bad ones? The book doesn't give a clean answer. But it leaves you with the feeling that maybe we've been looking for goodness in the wrong places. Not in perfect saints, but in flawed people sharing their one onion.

The young man's faith returns, but it's different now. It's not a belief in celestial proofs or incorruptible bodies. It's a faith in the sacredness of the earth under his feet and the profound grace of a single, shared kindness in the dark.

And maybe that's the only miracle we ever needed. It's not about whether our heroes fall. It's about whether we can find the courage to offer an onion to someone else who has. And to realize that, sometimes, we are the ones who need to be offered one, too.

Afterword: For Those Who've Walked These Pages

What I love about Alyosha—especially as someone who often sees him through the skeptical, smirking eyes of Ivan—is how unimposing his belief is. He doesn't preach. He doesn't debate. His faith isn't a position to defend. It's a way of being. He lives with kindness, not as a tactic but as a quiet wager: if goodness is real, it will ripple outward on its own.

It reminds me of that line often attributed to St. Francis: "Preach the Gospel at all times. Use words only when necessary." Whether Dostoevsky ever read it or not, Alyosha lives it. His presence is his testimony.

And yet, I'm aware of something I've missed.

As I was writing and rereading this section, I realized how little I engaged with Grushenka. She plays such a key role in Alyosha's turning point—many readers see that moment as just as much her redemption as his. I've seen entire discussions devoted to her character arc, to the complexity she brings.

But I have to admit: I didn't feel it.

At least, not yet.

I'm not sure if that's a flaw in the book or in me. Maybe I wasn't ready to see her clearly. Maybe I was too focused on the ideas Alyosha was carrying to pay attention to the person standing in front of him.

Either way, I'll keep thinking about it.